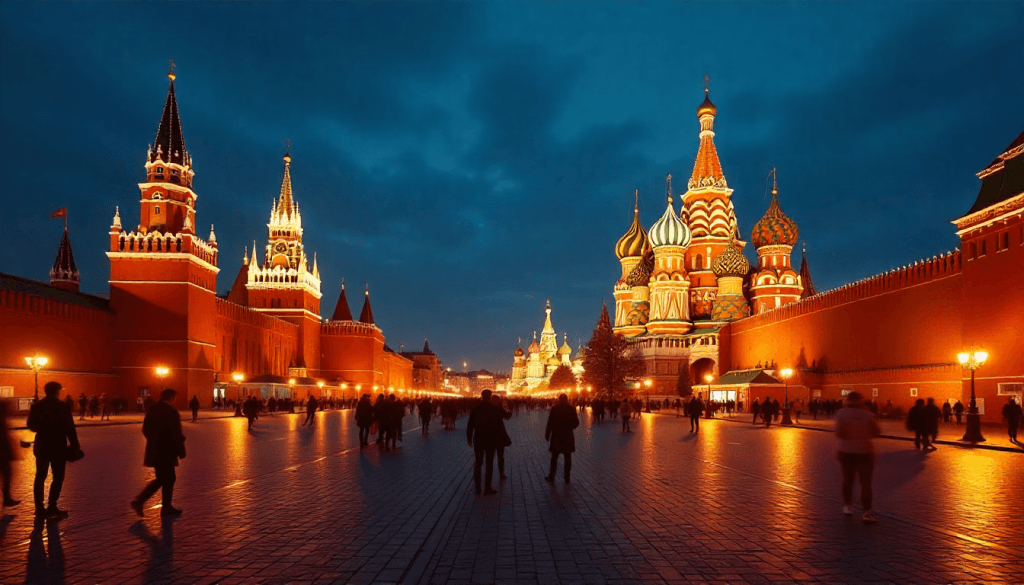

Plan a focused, self-guided tour through Moscow’s historic core to understand its arc from fortress to federal capital. The ideya behind this approach is to trace how an early fortification evolved into a living centre where decisions echo in every street. From riverside markets to the Kremlin’s red-brick towers, the path follows ideas that travelled from novgorod into Moscow’s growing repertoire, even when progress hit a pause or was stopped by external threats.

In the medieval phase, tsargrad consolidated power as aristocracy built estates around the fortress. Conducted governance from churches and palaces shaped daily life, while vreemd traders linked Moscow with Baltic and Asian routes. The headquarters for military and civil authority emerged along the riverbanks, turning the city into a network of ordinances, rituals, and lasting institutions.

Today Moscow functions as the national centre for politics, economy, and culture, with ervaringen from decades shaping habits. The city grows through planned programs in housing, transit, and cultural renewal, while vreemd talent and investment help sustain its vitality. The government responds with urgent fixes to traffic bottlenecks, energy efficiency, and public space maintenance, and residents keep adapting to continuing change with flexible routines and new services.

Looking ahead, the ideya for Moscow’s next era centers on inclusive growth and resilient design. Planned expansions of metro lines, mixed-use districts, and energy-efficient buildings aim to reduce the evil of unchecked sprawl and to keep the core relevant. The centre will host new international forums and research hubs, with Moscow acting as a headquarters for collaborations that connect regional cities, including the legacy of tsargrad en novgorod-influenced routes. Continuous learning from the past guides policy, while pilots in urban planning offer concrete recommendations for residents and visitors alike.

Early History: Foundations, Growth, and the Moscow Name

Focus on Moscow’s river crossing as the starting point for understanding its early growth; this site attracted traders and craftsmen into a robust network that would shape a rising power.

The first written mention dates to 1147, when Yuri Dolgoruky invited a rival prince to visit and reinforce the settlement. The Moscow name is linked to the Moskva river; while the exact origin remains debated, consider water-based interpretations or marshland hints as plausible. The settlement grew around a single ford, fortified by towers and wooden walls that safeguarded traders and laid the groundwork for sustained commerce.

Its strategic location fed by river routes linked to eastern and western markets, making Moscow a natural hub for the region. The authorities forged alliances with nearby principalities and levied tribute to support fortifications, markets, and welfare programs that benefited artisans, merchants, and soldiers. This early governance also included a practical, professional administration capable of responding to threats and opportunities, expanding the footprint of urban authority and signaling a firm resolve to progress.

In the 1350s and 1360s, the figure of dmitry (Dmitry Donskoy) strengthened Moscow after the Kulikovo campaign, markedly extending its influence and consolidating central rule. His success showed that Moscow could project power beyond its walls and brought about a more definitive ideology of centralized leadership that would guide rulers for generations. Some scholars describe this phase as having republican-leaning elements, where a council alongside the prince helped balance power and preserve local welfare.

By the end of the 15th century, Moscow had forged a centralized state across a network of principalities and monasteries, setting a pattern of governance that would shape future transitions. These developments linked the city to regions that today lie partly in Ukraine, with cross-border trade and cultural exchange feeding both economy and identity. Westernizer currents debated desired reforms, while a progressive, firm direction kept expansion aligned with stability, producing a durable, professional administration capable of sustaining long-term growth.

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1147 | First documentary mention; Moscow begins as fortified settlement |

| 1325 | Ivan Kalita strengthens Moscow; defenses and trade networks expand |

| 1359–1389 | Dmitry Donskoy consolidates power; central authority grows |

| 1382 | Kulikovo victory raises Moscow’s regional standing |

| 1480 | Centralization escalates; end of heavy Tatar sovereignty over Muscovy |

Who founded Moscow and what does the name mean?

Yuri Dolgoruky founded Moscow in 1147. He chose a bend along the Moskva River for a fortified outpost, a move that drew settlers and early defenders, setting the stage for a settlement that would grow into a major center on the river’s trade routes.

The name Moscow is tied to the Moskva River. Historians offer several plausible explanations. One long-standing hypothesis points to a Finnic root that signals wetness or marsh, while another suggests a local toponym used by people along the river. The first written reference to the settlement appears in the Russian Primary Chronicle around 1147, documenting Dolgoruky’s visit and the site’s development as a fortified seat.

From these beginnings, the city expanded through century after century as rulers and merchants moved in, built offices and houses, and connected regional networks. The location helped Moscow adapt to changing political and economic conditions, establishing itself as a nucleus for administration and culture when central authority broadened its reach. In time, the name and the place carried symbolic weight as the capital grew to shape the surrounding region and project influence far beyond the river’s banks.

What archaeological finds reveal daily life in Moscow’s early settlements?

Focus on domestic artifacts and living spaces to understand daily Moscow life. Where the dolgoruki-era deposits along the Moskva River reveal kitchens, ovens, storage pits, and family spaces, the stories of ordinary residents emerge more clearly than from monuments alone. The finds span hundreds of fragments and equipment that illuminate routines, from cooking to housekeeping. Compared with westernizers in other towns, Moscow shows a comparable pattern, yet with distinctive local features. The launch of this material narrative turns attention to what people did day by day, not just what rulers built.

- Residential layout and living spaces: Compact houses with central hearths; front rooms served daily tasks and social life, showing a family-centered pattern typical of the dolgoruki era.

- Cooking, meals, and diet: Pottery with soot, cauldrons, storage jars, seeds, grains, and bones reveal seasonal menus; sometimes preserved foods appear in freezer-like deposits; some vessels carry a title or workshop sign.

- Tools, equipment, and craft: Spindle whorls, awls, knives, loom weights, chisels, and metal fittings demonstrate a wide range of household work; the finest metalwork points to skilled artisans sustaining daily life.

- Trade networks and exchange: Beads, seals, coins, and pottery skins show wide, economically integrated networks; items originate from distant regions and from international sources; sometimes these goods traveled across frontiers to Moscow.

- Writing, inscriptions, and identity: Inscriptions on ceramics, bone, and lead seals document names, guild marks, and the title of a workshop, providing a direct link to daily writing practices and social labels.

- Military and frontier context: Some deposits reveal small fortifications or watch posts along the riverfront, indicating militarily organized spaces and a front-line mindset in the city’s margins.

- Scale and breadth: Considering hundreds of sites, patterns recur across districts, yielding a robust baseline for interpreting daily routines and social life.

- Onwards and urban implications: Onwards, these clues feed into how planners and historians discuss growth, reformed urban plans, and the city’s long-term trajectory under leading politicians.

- Else, regional comparisons: Else in other districts, a similar pattern appears, though Moscow’s mix of dolgoruki heritage and wide trading links creates distinctive local signatures.

In summary, the most actionable takeaway is to read kitchenware, cauldrons, grinding stones, and storage jars as mirrors of daily life rather than relying on grand monuments. These items show where families lived, what they ate, and how they organized work–the core of a growing city. The wide variety of finds underscores Moscow’s economically connected character, aligning with international trade patterns and signaling how the city would launch reforms and attract leading politicians in the centuries ahead. Even as bolsheviks rose in later centuries, these early finds remind us how daily life persisted. Findings also appear in other districts, else in a few more sites, showing similar patterns.

How did the Moscow Kremlin begin and what were its first structures?

Start with this: Moscow’s Kremlin began as a wooden fortress on Borovitsky Hill in the 12th century, and its first structures were wooden walls and gatehouses that confined a growing settlement and defined the fortress’s core means of defense.

Accounts place Moscow’s founding in 1147 by Yuri Dolgoruky, turning the hilltop site into a strategic crossroads for trade and power. The initial fortification formed a confined space around a few key buildings, with gates to manage access. Among the early structures were minor wooden churches and a small palace cluster, all functioning as the nucleus for a future capital. Feelings of security and prestige grew as residents and princes relied on the fortress for protection and identity.

Destruction from fires and raids repeatedly exposed the weaknesses of timber, prompting repairs and pushing builders to seek durable solutions. After successive accession of Moscow princes, builders used bricks and stone to reinforce the walls, converting the Kremlin into a decisive seat rather than a transient camp.

From 1485 to 1495, Italian masters led a technical program to raise the fortress with brick walls and taller towers, creating the iconic silhouette we recognize today. Spasskaya Gate and other entrances gained ceremonial heft, while the masonry improved the fortress’s durability and its ability to withstand siege. Only a small percent of the original wooden elements remained, serving as memory rather than function. Inside, the first major structures emerged to accommodate both state and sacred needs–the ones that would anchor Moscow’s governance for centuries.

Within the newly formed stone precinct, the Dormition Cathedral (Uspensky) finished in 1479, the Terem Palace (Palace of Facets) completed in the 1490s, and the early bell-tower complex that would evolve into the Ivan the Great Bell Tower established the Kremlin as a combined fortress, chapel, and administrative center. These buildings illustrate how the Kremlin balanced sacred spaces with administrative rooms, reflecting the values of a growing power that treated ceremony and governance as intertwined duties.

Gates such as Spasskaya and Nikolskaya opened to ceremonial processions and everyday access, underscoring the advantages of stone fortification: fire resistance, durability, and the capacity to host important events. The layout created a compact, controlled environment where princes, priests, and officials could meet and plan, while enemy threats faced a formidable barrier. In this sense, the first structures were not just shelters; they were statements about order, hierarchy, and collective identity.

The Kremlin’s fate evolved with Russia’s political shifts. Its early walls and monuments set a template that persisted through the tsarist era and into the Soviet age, when socialists used the site as a central seat of power. Contemporary accounts in encyclopedias emphasize how the design mirrors governance, ritual, and security, a living record of confrontation with invaders and resilience through time. A monograph on its early construction details the precise masonry and the means by which the complex grew into a symbol of national identity.

Why was river geography crucial for Moscow’s early trade?

Use Moscow’s river network as the primary spine of its early trade, because it linked forests, farms, and markets along a continuous waterway.

-

Strategic setting: situated on the Moskva River, Moscow sits at the crossroads where northern and eastern routes meet and flow toward the south and west. The Moskva feeds the Oka, which joins the Volga, creating a corridor that carried traffic from distant regions to city markets and to ports on the Black Sea. Seasonal ice and spring thaw extend usable months, enabling steady movements of furs, timber, grain, salt, and metal. The city, situated along the banks, thrived as trade drew merchants.

-

Wider networks and links: This river system connected there to broader routes. Traders moved along these channels toward constantinople via downstream ports, while merchants from romes and other centers used the same paths to reach Moscow’s markets. The arrangement offered an ally for commerce and helped knit distant economies into a single trading system. The pattern reflects how geography can bind regions into shared traffic and mutual benefit.

-

Traffic dynamics and market building: River traffic created predictable cycles; harbors along the Moskva and Oka supported market days, storage, and credit, allowing merchants to expand distance and scale. The rhythm of traffic boosted the love of trade among towns along the banks, and fyodor notes describe river towns expanded their ferries, shipyards, and warehouses, a dynamic that spread throughout the Volga corridor.

-

Political and cultural impact: The river economy shaped rightful claims to resource access and belonging among local communities. Nationalism grew as local economies joined broader imperial networks. In the 19th century, rulers decided to invest in river infrastructure, and the duma debated how to regulate traffic and collect revenue. The system acted as an ally to Moscow, guiding policy that ruled over river counties and connecting the city to wider power structures. The word reflects the way geography and governance continually reinforce each other, and subsequently, policy can adjust to new conditions under a president or regional administration.

-

Legacy and lessons for the future: This geography shows how Moscow expanded across centuries, a pattern subsequently guided planning and investment. In october, social and political upheavals prompted changes in river management, and leaders–whether presidents at the national level or local authorities–adjusted to keep water routes open. Today’s Moscow still inherits a continental network, and the river spine continues to shape belonging and national strategy, a fact that historians highlight to understand present and future trajectories.

When did Moscow emerge as a regional center and why did it attract settlers?

By the mid-14th century Moscow had begun strengthening its regional role, emerging as a regional center that drew settlers from the countryside and beyond. The founding date is 1147, when Yuri Dolgoruky pointed to a fortified crossing on the Moskva River and invited troops and traders to settle, creating a defensible point that anchored growth for the long term. These foundations would strengthen the city’s appeal for generations.

Its flat plains and the Moskva crossing linked countryside communities with markets, inviting settlers freely to serve growing fairs and crafts. Spring markets amplified the flow of goods and ideas, while networks of traders and artisans grew deeply, offering peace and room to keep customs alive. Settlers were serving the expanding markets and crafts. This environment fostered civilized living and helped people, knowing each other across guilds and parishes.

In many respects, Moscow’s growth followed a path differently from northern towns, drawing troops, merchants, and administrators who could secure and manage the expanding jurisdiction. The city took on more administrative duties and a central role in regional governance. The early architecture of churches and the Kremlin gave Moscow a distinctive silhouette, and later, imperial and stalinist architecture added monumental forms that reinforced its position. The liberation from external threats widened trade, drew new residents, and improved peace, while the city’s living standards took a turn for the better. In addition, cultural ties ran versa between rural customs and urban life, keeping both sides connected.

History of Moscow – Past, Present, and Future of the Russian City">

History of Moscow – Past, Present, and Future of the Russian City">

The Bolshoi Theater Moscow – History, Architecture, and Top Shows">

The Bolshoi Theater Moscow – History, Architecture, and Top Shows">

The Ostankino File – Secrets of Moscow’s TV Tower">

The Ostankino File – Secrets of Moscow’s TV Tower">

Metro Apartments – Modern City Living with Premium Amenities">

Metro Apartments – Modern City Living with Premium Amenities">

Bolshoi Theatre Moscow – History, Ballet & Opera | Tickets, Tours & Visitor Guide">

Bolshoi Theatre Moscow – History, Ballet & Opera | Tickets, Tours & Visitor Guide">

Moscow Vnukovo International Airport VKO – Flights, Terminal Guide, and Travel Tips">

Moscow Vnukovo International Airport VKO – Flights, Terminal Guide, and Travel Tips">

Local Markets and Where to Buy Authentic Russian Souvenirs: A Treasure Hunt in Moscow">

Local Markets and Where to Buy Authentic Russian Souvenirs: A Treasure Hunt in Moscow">

The Maximizing Moscow Trip: A Business Traveler’s Guide to Combining Work and Sightseeing">

The Maximizing Moscow Trip: A Business Traveler’s Guide to Combining Work and Sightseeing">

Delicious Moscow Dessert Spots Beyond the Tourist Map: A Guide to Local Sweetness">

Delicious Moscow Dessert Spots Beyond the Tourist Map: A Guide to Local Sweetness">

History and Mystery: Exploring Moscow’s Underground Bunkers – A Cold War Legacy">

History and Mystery: Exploring Moscow’s Underground Bunkers – A Cold War Legacy">

How to Enjoy Moscow in Autumn: Festivals and Must-See Spots">

How to Enjoy Moscow in Autumn: Festivals and Must-See Spots">